There will be a day in the future when memory downloads into computers will enable this to happen, but in the meantime consider: There is satisfaction in planting some seeds of wisdom, history, and knowledge in the form of pictures, stories, and facts about our families and friends.

While we enjoy reasonably good health and have sufficient enough gray matter (or marbles), it might be worthwhile to document some our own history and memories. Your life will have been etched on parchment or in cyberspace, not easily buffed away especially if stored electronically. They represent your legacy, your mark in their world that carries your persona. Pictures bring meaning to words and words enhance the pictures. Our children, grandchildren, great grandchildren, nieces, and nephews will treasure the documents and pictures that you “will” forward. In Lincoln’s early years, “…he was more than willing to die, but he had ‘…done nothing to make any human being remember that he had lived.’” Obviously, he later had done much in which to remember him. Abraham Lincoln summarized that desire in a quote from the book, “Leadership in Turbulent Times” by Doris Kearns Goodwin. We all have a basic desire to leave a mark, a piece of ourselves that triggers a memory in someone years after we are gone. There is also comfort for us, the autobiographers, knowing that our lives will be remembered. I missed my one last chance to learn more about my father and there will never be a way to get that chapter of his life. I had never heard much about this time in his life, but I was exhausted that night and eager to get home to my family. On the evening before an operation that would deprive him of his ability to speak, he seemed anxious to tell me about his days as a young man working on ranches and farms in the Dakotas.

I have written in the past about my dad’s final days before he died. Even a few handwritten notes might have served as fragments like the ancient Egyptians left behind in their drawings and hieroglyphics on papyrus scrolls. We shared our time on earth only so briefly, leaving only vague, blurred memories, few pictures, and no documents. Likewise, I wish that I could better remember my two grandfathers better. But for those who are open to talk about themselves, there are some fascinating tales. Some may bore you to tears, some will keep their earbuds on (don’t ask them). Why do I think that everybody has a story? Just ask a complete stranger in an airplane (if they are willing) a few questions. Stories add multiple dimensions to an otherwise nondescript name in the census tally. Everybody has a story, and every story may be important and meaningful to our descendants.

Oral tradition was particularly effective in societies vastly different than ours, but even in ancient times basic documents were written, and records were kept.įor the sake of the next generation and those following, it would be helpful to pass on a “life will” that has our stories in writing and pictures. Our stories have been told in a scattered mode over a number of years. Which brings me to the point about writing.Ĭhildren usually have only superficial knowledge of their parents’ earlier years including work history. Nowadays, I play a different game and hope to maintain my current level of marbles. Every day I hoped to keep my marbles and add a few.

USE LOSE YOUR MARBLES PLUS

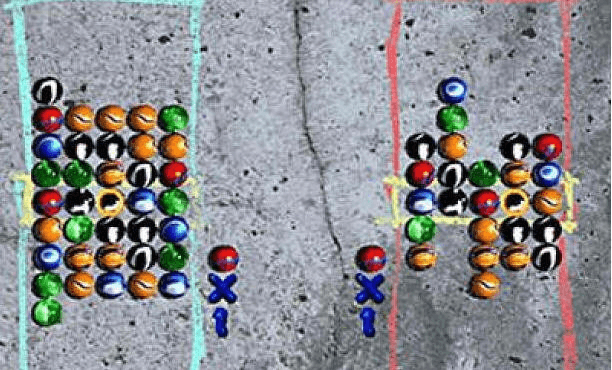

My bag included about 20 or so glass marbles that included a “boulder, a steelie, shooter, a puree” plus others. It’s a good analogy because I played “mibs” when I was in St. “You might have put it a little differently, son, but I get your drift.” My mother, Adele Ginter Kennedy, her siblings, and classmates circa 1925 playing marbles.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)